🌹 🎶 Reverberating Voices

An Ancestral Ramble through Deptford Literature Festival

In the early hours of 7th January 1928, my maternal Grandad Percy, the hearing child of two deaf parents, was awakened by banging on the door of their home at 70 Evelyn Street, Deptford. “Upon looking out I saw a few men wading in four feet of water that lapped our houses. It was not raining but they shouted “Tell yer Mum and Dad - there’s a flood!” Whilst rescuing the cat and family dentures from the black copper downstairs in the kitchen, my great-grandfather, Percy, dropped said teeth and had to plunge naked into the cold waters to retrieve them, before retreating upstairs, shivering violently. As the cat had soaked Grandad’s bed, Great-Grandmother Clara gave up her place so son and father could keep warm -“she greeted the morning alone as the tidal waters ebbed from the houses and streets and returned along the river.” Famed in both London’s and my family’s history, the flood led to the construction of the Thames Barrier in the 1970’s.

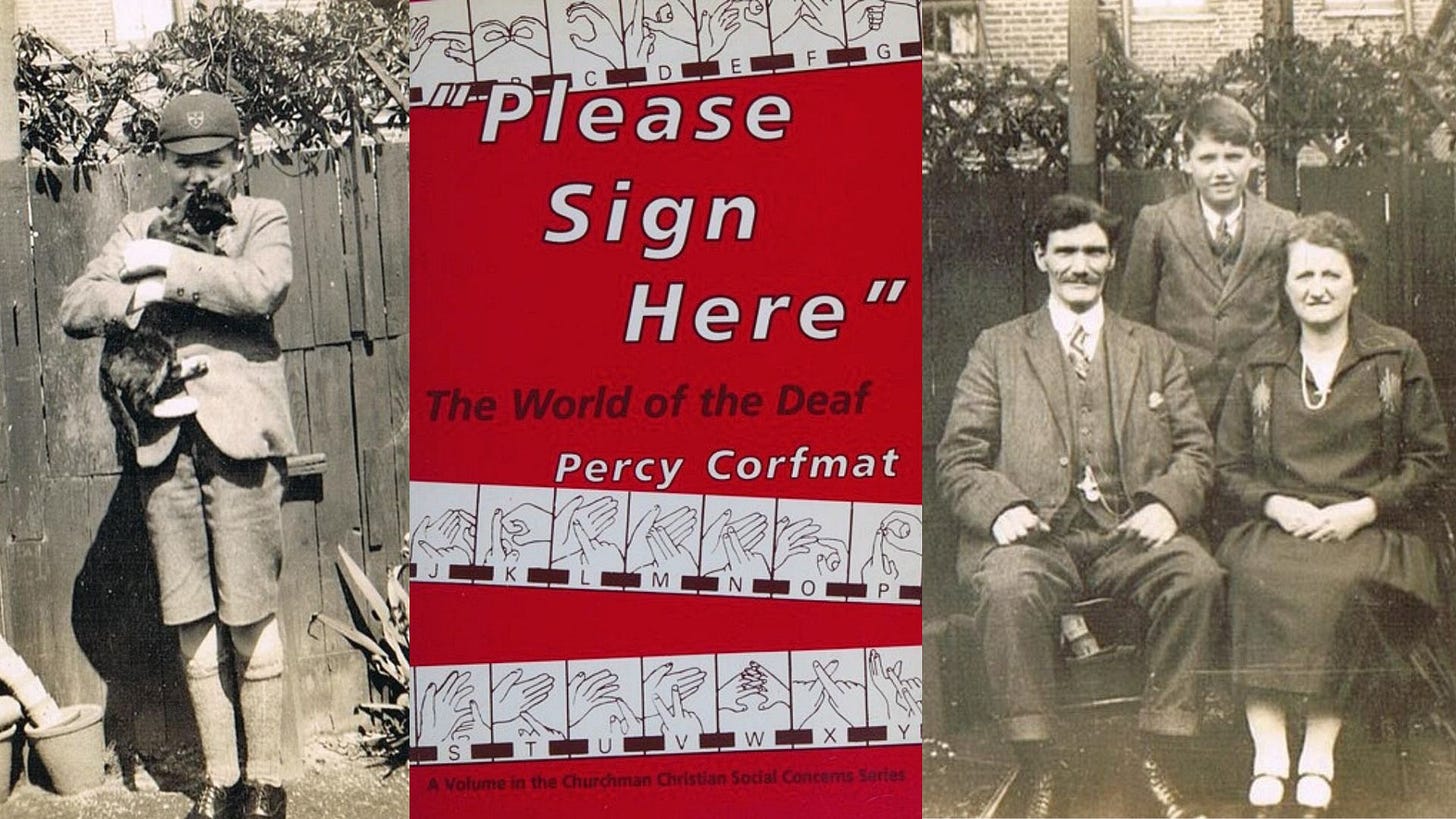

*My Grandad, Percy & Cat 1928 *His book, Please Sign Here 1990 *Percy, Percy & Clara 1928

My Grandfather’s book - Please Sign Here - The World of the Deaf (1990) - opens with a vivid description of the sounds of “Deep Ford” - the “clopping horses pulling their heavy loads over the cobbled roads,” the “ships noises of different nations,” the “sharp metallic sounds” of the locomotives and “the factory hooters that summoned and expelled their army of workers.” This soundscape was vitally alive to him but silent to his parents, so he became a child intermediary between the hearing and deaf worlds, and later a Pastor for the deaf. As signed voices fell on deaf ears in the often cruelly uncomprehending hearing world, his book advocates for the use of BSL (British Sign Language.)

Deptford Literature Festival - where I attended sessions on Yoga & Books, Deptford’s Buried History, Music & Books and the Audio-Walk, 16th March 2024

Almost a century after the flood, I’m soaking in words at Deptford Literature Festival, watching the fluid hands of BSL interpreters send silent reverberations rippling through the air alongside spoken voices. Dissolving on a yoga mat, I bathe in music, words and gentle movement and writing prompts from sisters Gemma and Laurie Bolger, my eyes misted by this soothing, soulful welcome back to Deptford.

The festival reverberates with voices past, present and future. Circling the skull-topped gates of St Nicholas’ Church, writer Jody Burton masterfully excavates Deptford’s Buried History. Married at the church in 1512, we hear how black trumpeter John Blanke, employed by Henry VII and VIII, took part in the Westminster Tournament of 1512. The Church Banners, Jody says, list the ships built in Deptford Dockyards between 1513 and 1869 without acknowledging their role in the transatlantic slave trade. Of 36,000 slave voyages globally, 3,000 set sail from the stretch of Thames between Greenwich and Deptford.

Deptford resident John Hawkins was the first British slaver and initiator of the ‘Triangle Trade’ between Europe, Africa and the New World. After an initial lucrative voyage, he gained the backing of Elizabeth I and was awarded a coat of arms bearing the image of a slave. His voyages with Sir Francis Drake between 1562 and 1569 enslaved 1,200 Africans, which would have involved killing three times as many.

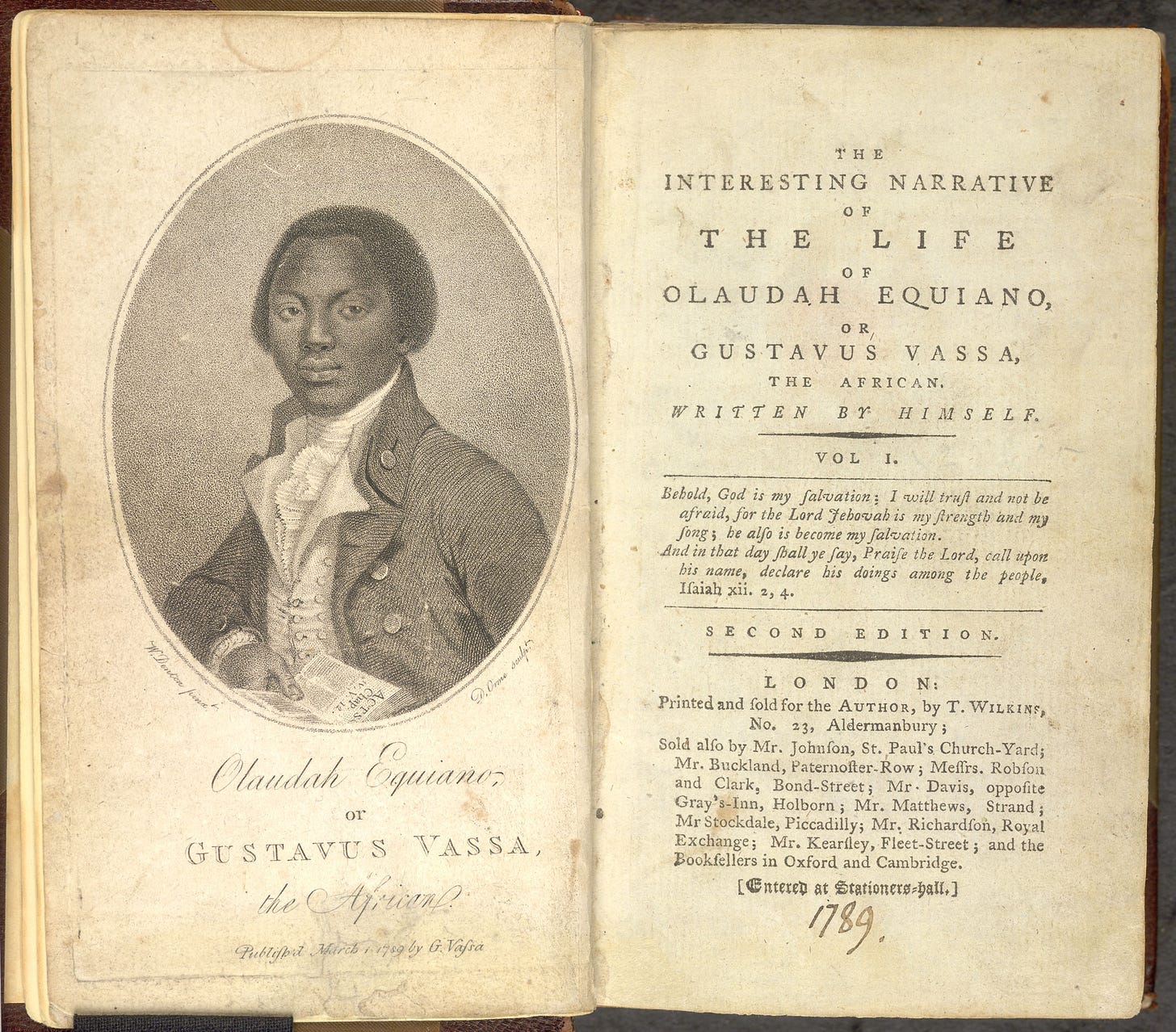

“But is not the slave trade entirely a war with the heart of man? And surely that which is begun by breaking down the barriers of virtue involves in its continuance destruction to every principle, and buries all sentiments in ruin!”

Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vasa, The African, Written by Himself (1789)

Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797) described the situation onboard slave ships as “a scene of horror almost inconceivable.” Over 12 million slaves were transported across the 80-day ‘Middle Passage’ between Africa and the New World, of whom an estimated 4 million died. Captured and enslaved in Nigeria with his sister, Olaudah worked on a plantation in Virginia, before being sold to Royal Naval Captain Pascal, in whose Blackheath home he was educated. He sailed from Portsmouth to Deptford in 1762 and was sold to Robert King, from whom he bought his freedom in 1766. He escaped further attempts to capture him, working as a sailor and raising a family in London, where he became a leading Abolitionist. In Chapter 1 of his best-selling autobiography he writes: “Olaudah in our language, signifies vicissitude or fortune also, one favoured, and having a loud voice and well spoken.” His heroic voice continues to reverberate on behalf of millions who were silenced.

When slavery was finally abolished, 36 years after Olaudah’s death, the British Government issued £20 million in compensation payments to 25,000 existing slave owners. Research shows that areas of Britain involved in slavery profited from economic expansion during the Industrial Revolution. Gloria Daniel, the great, great granddaughter of John Isaac Daniel, enslaved on Thomas Daniel’s plantation in Barbados, set up the TTEACH 50 Plaques and Places campaign for black plaques to be placed on buildings, churches and institutions associated with the Transatlantic slave economy. The first plaque, Jody tells us, has been installed at Deptford Town Hall where the exhibition continues until 24th March. As Convoy’s Wharf is swallowed up by property developers, a pioneering community group is campaigning for a Museum of Slavery and Freedom (M ō S a F) at the site of the Royal Naval Docks to ensure the full story of Deptford’s involvement in slavery and abolition is told.

After a delicious soul box lunch with a friend at Chai Wrap, I drift on the words of James Wilkes and Joe Rizzo Naudi’s Sounding Deptford Audio-Walk, feeling like a piece of flotsam floating on all that has washed in and out of Deptford.

“I met people who never quite fit in where they were supposed to, who found solace, salvation and meaning in these sounds, these words.”

- Aniefiok Ekpoudom - Where We Come From: Rap, Home & Hope in Modern Britain

Music as both a transformative force and a roadmap of social history finds powerful advocacy in the writing of three authors and their books - Aniefiok ‘Neef’ Ekpoudom - Where We Come From: Rap, Home & Hope in Modern Britain, Emma Warren - Dance Your Way Home and Jacqueline Crooks - Fire Rush, in a far-ranging discussion hosted by writer Natty Kasambala. As they reflect on the sensitivities of documenting living, breathing communities, it’s clear they share a powerful drive to tell unheard stories. Jacqueline Crooks sets her novel in the Black Sound Revolution of the 70s & 80s, describing underground dub-reggae venues as “transportative, liminal spaces” for black communities invisibilised in a hostile environment. Neef charts the evolution of rap and grime as inseparable from the political and personal histories of black musicians in South London, the West Midlands and South Wales. Reflecting that time is slippery in writing, Emma Warren urges us to continue the empowering, liberating process of storytelling - to share “the blessings of what we make with the future us.”

Leaving the Festival, I pause infront of the beautiful Heart and Soul mural and its slogan ‘We Believe in the Power and Talents of People with Learning Disabilities.’ There were no slogans celebrating the marginalised signed voices of my great-grandparents a century ago, but their stories and those of their deaf community were preserved for the future me in the blessing of my Grandad’s book. I zip up my coat to fend off the March breeze and head along Deptford High Street, feeling inspired and invigorated by the reverberating power of words - signed, spoken and written.

ANCESTORS

Your ancestors did not survive

everything that nearly ended them

for you to shrink yourself

to make someone else

comfortable.This sacrifice is your warcry,

be loud,

be everything

and make them proud.